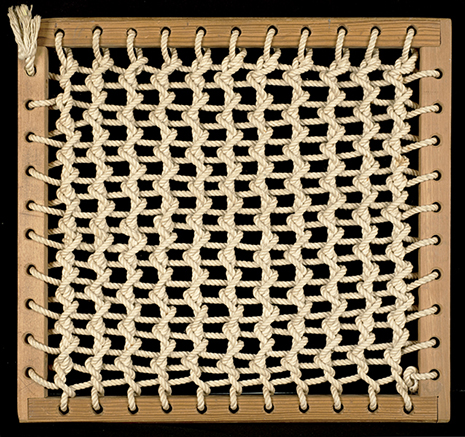

5 STITCHES PER WINDOW

1040 STITCHES PER OFFICE FLOOR

80 ON OUTER FACADE X 4

90 ON INNER FACADE X 8

44,720 STITCHES IN TOTAL (CURTAIN WALLS)

3,440 BY OUTER FACADE X 4

3,870 BY INNER FACADE X 8

“If one were to separate art and knowledge at two ends, somewhere in the middle you would find craft: where art, knowledge and skill interlace.”

“...imagine an architectural analysis in which repetition replaces opposition as a critical tool, relentlessly articulating the circuitries of control implied by the modular, patterned cascade, as well as the networks of power and knowledge that make it possible.”

This provokes a central question of scale: What happens when we keep the form, but change the materiality of an object? What happens when we can hold a skyscraper in our hands?

In The Organizational Complex, Reinhold Martin argues that "the architecture of the curtain wall is a medium to be watched in passing rather than looked at like an artwork" (Martin 6). This certainly holds true when we physically encounter buildings like Place Ville Marie, Modernist structures evoking the sublime which we can never take in all at once; which we necessarily encounter in transit, in fragments.

In the finished articulation of my stitched Place Ville Marie, you will be able to hold the building in your hands, manipulate it, view it from every angle. Musing on the 1922 publication of the journal De Stijl, Martin finds that the journal expected art photography "to produce new optical relationships, and not merely reproduce what already exists" (47). This, I argue, is necessarily what happens when we transmute an object from one form to another--we create something which is entirely new, yes, but which simultaneously is in direct, unavoidable conversation with its predecessor.

Having worked in textile arts for years, both as a crafter and a conceptual artist, I came to this project with an experiential, embodied understanding of the grid as a design tool. As an academic and artist, my praxis inevitably involves making as a way to comprehend thoughts by transforming them into physical objects which give them structure and context. The majority of traditional textile arts--from weaving, to knitting, to cross stitch and needlepoint--are designed on a grid system. By nature, these designs are easy to replicate and tend to be shared publicly, often for free, highlighting the role of collaborative making in textile arts

The similarities between textile and architectural design are rich--the formal specificity inherent to their design and articulation along grid systems; their liminality within the contexts of fine arts and design; the necessity of long-term, often collaborative labour in the creation of their material structures, and the cultural gendering of these differing labours. My first impulse was to rebel against the materiality of Place Ville Marie, to create a cuddly pink version of the cold, Modernist structure. But I soon found the theoretical dis/similarities to be more compelling territory.

An architectural design, like a needlepoint design, is made with the express intention for it to be reproduced. These acts presuppose collaboration.

Using my designs, another person could easily create this stitched version of Place Ville Marie. However, in this articulation of the project, unlike the architect, I am also the maker. I wonder, how are the politics of making complicated when these roles are fused? How are different materials and forms of labour assigned different values (ie, the architect vs. the construction worker; the construction worker vs. the stitcher)?

47 FLOORS; 43 OFFICES

208 WINDOWS PER OFFICE FLOOR

16 ON OUTER FACADE X 4

18 ON INNER FACADE X 8

8944 WINDOWS IN TOTAL

688 ON OUTER FACADE X 4

774 ON INNER FACADE X 8

By comparing specs of the building against visual references, I created a gridded to-scale system on which I could design Place Ville Marie in the style of 'needlepoint on plastic canvas'. Three 'units' vertically on the plastic grid equal approximately one floor of the building. I began by designing the iconic twelve exterior 'curtain walls'. Using exact building specifications and measurements, verified against visual references, I designed the walls with a focus on replicating the forty rows of black windows. The interior walls contain rows of 18 windows, rather than the 16 windows of the exterior walls, as well as an extra column where they meet at the four interior points of the cruciform.

From there, I was able to design the roof and its structures, as well as the bottom structures of the RBC buildings, the glass entrances, etc. The bottom of the structure was the most challenging to design as there are several ledges which jut in and out around the base. As a Modernist building emblematic of the International Style of architecture which models its designs around central steel beams baring the weight of the building, this makes no difference to the structural integrity; the 'curtain walls' are decorative and can be made largely of glass. However, in my design, the 'curtain walls' bare the weight of the structure, and so the final product may have to be internally reinforced in order to stand solidly.

In her seminal essay "Grids" (1979), Rosalind Krauss sees the grid as necessarily oppressive, arguing that "the grid announces, among other things, modern art's will to silence, its hostility to literature, to narrative, to discourse" (50). While I can appreciate her anger, a valid product of her artistic-historical circumstances in which little space was made for the voices, experiences, and artistic mediums of women, her claim that the grid appeared "nowhere, nowhere at all, in the art of the [nineteenth century]" (52) completely invalidates the huge amount of stichcraft and other textile arts produced by women in this period--within the Western world, but also worldwide. Even the Modernist grid does not, as Krauss argues, necessarily silence. You only have to look as far as her contemporaries, female textile artists in the midst of a boom in feminist conceptual arts, to see the revolutionary conversations being had in regards to women's subjectivity, gendered materials and labour, and anti-oppressive practices in art and arts organizations.

I argue against the gendered materiality of the grid. The grid is a tool, not necessarily masculine or oppressive, which has been used by women for millennia to create artistic works which reflect their daily lives and experiences.

You cannot speak about grids in fine arts without speaking about Agnes Martin. You cannot speak about the legacy of Josef Albers without speaking about the ingenuity of Anni.

“Though grand, her grid paintings were created from small repetitive gestures and simple means. They required a painstaking and labor-intensive process”

Artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles named these labours 'maintenance work': the feminized, devalued work of sustaining the lives and spaces in which masculinized, valued innovation occurs. In "Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!", she identified "the sourball of every revolution: after the revolution, who's going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?"

Helen Molesworth later synthesized Ukeles's concerns when she critiqued the societal notion of gender equality which "(as found in much Anglo-American feminist theory) reveals the very notion of equality and its symbolic representation in the pubic sphere to be historically dependent on the unacknowledged (and unequal) labour of the private sphere." ("House Work and Art Work" 76; emphasis mine).

“She is silent when she sews, silent for hours on end…she is silent, and she – why not write it down the word that frightens me – she is thinking.”

stitching as a craft as inherently, historically meditative

- realizations are born through praxis

- Slow Stitch: Mindful and Contemplative Textile Art

- though not uncorrupted by corporitization (the invention of the sewing machine, fast fashion)

- the insistence of 'faster is better' has nothing to do with human actualization/satisfaction but with capitalistic production/corporate productivity

"slow time"

- "living the fast life instead of the good life" Carl Honore's In Praise of Slow

- Suzy Lake's one-hour exposures

- slow architecture movement + slow cities movement

- Lisa Robertson's Office for Soft Architecture

slow time vs. corporate space

- stillness vs. movement

- to embody a corporate space properly is to move through it efficiently (see Corridor, Kate Marshall + my own experience of stillness within the channels of PVM's central elevator block) )

- rejecting the "no standing still" model of excellence (The Slow Professor 8)

The 1970s saw a movement of women creating feminist conceptual artworks. Reacting to minimalism, modernism, and a male-dominated art world which devalued 'women's work', these artists deliberately used highly textured and brightly patterned materials, often through practices such as textile creation and collage which were dismissed in fine arts for their associations with femininity.

Works such as those in Elaine Reichek's series Laura's Layette incorporate transformations of knitting patterns into pseudo-architectural schematics, placed into visual comparison with the completed knitted work. Reichek's piece Pyramid furthers this practice by placing a knitted wearable into direct visual comparison with architectural geometries. This meticulous work succeeds in highlighting the similarities in the labours of knitting and architecture, while playfully critiquing their gendered divides. Like artist Mary Kelly, who documented the bodily functions of her son for the first seven years of his life in Post-Partum Document, Reichek and other feminist artists of the time were concerned with the devaluation of women's time and labour.

Modularity in Modernism (Suprematism, Bauhaus, De Stijl)--carried over into modularity within corporate architectures

What is the proper/improper or normative/non-normative way to embody spaces?

- questioned within embodiment of gallery spaces

- ex, LeWitt vs. Pepe

- Suzy Lake performing "maintenance work" as art within construction/gallery site

- carries over into strict, normative embodiment of corporate spaces

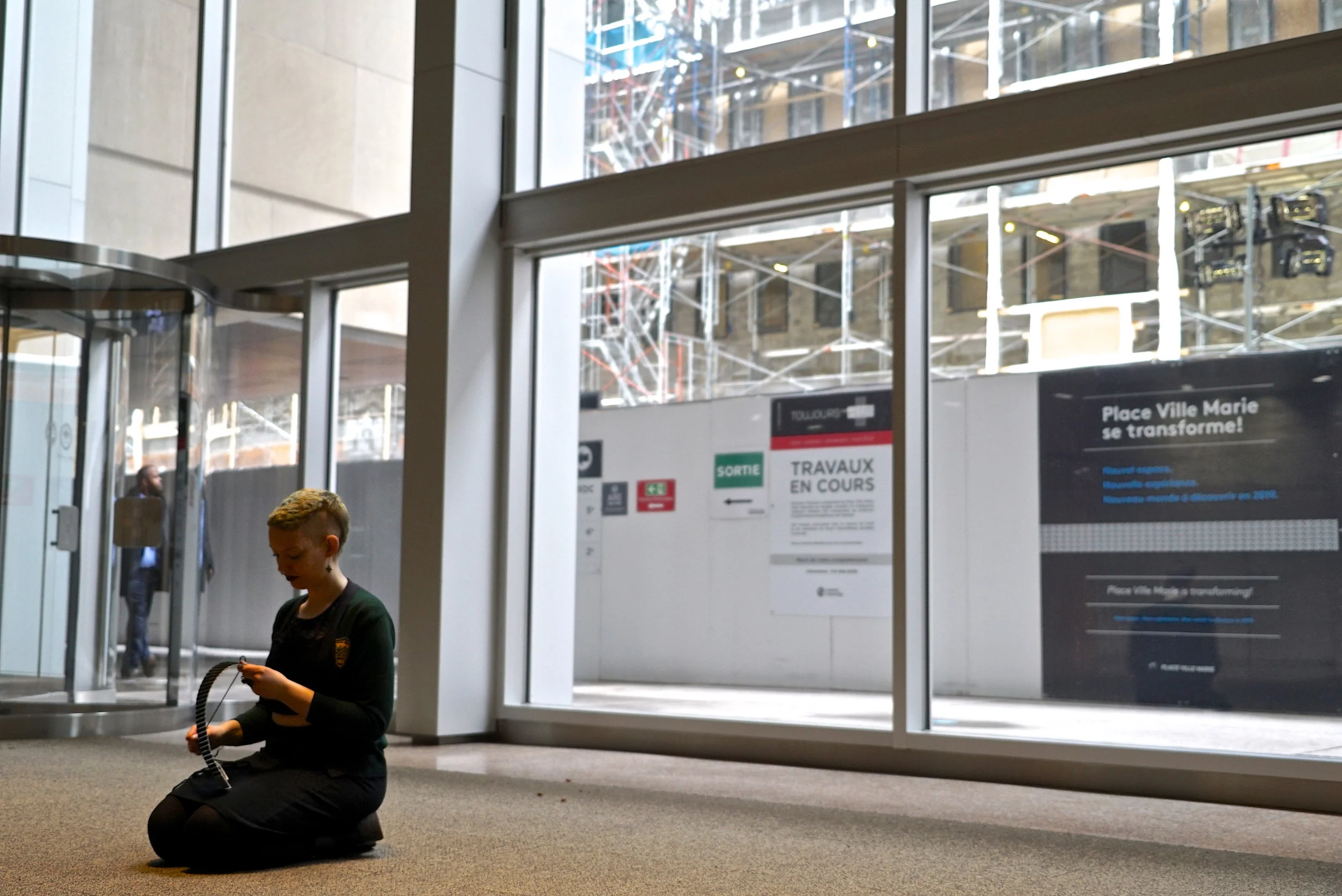

Feminist conceptual artists created work and continue to create work which makes visible the invisible labour of women and the time & space which it takes up, often, as Molesworth observed, by juxtaposing this divide of the public and private. In my performance of Place: A (Re)construction, this is why I reframe the private, feminized, devalued labour of needlework into the corporate, masculined, capitalistically valued space of Place Ville Marie. However, as I embodied this space, I couldn't help but notice the significant presence of construction workers both around and inside of the building--the similarities of their labour with mine and their striking displacement within this space which they are integral to creating and maintaining.

architectural construction as a form of gendered labour , comparable to needlework

- in both forms of labour, it looks like nothing is happening when observed by those without knowledge of the craft--both take a very long time to complete, looks like nothing is happening

- very small vs. very big--many small steps towards a complex whole

- neither construction worker nor stitcher visually fit into the corporate channels--we are slow (yet not necessarily inefficient)

I have argued that 'women's work' is collaborative (ex, sharing patterns), but in comparison to the direct, large-scale collaboration of architectural construction, it appears isolating...

the space of making (construction site) as heavily restricted access [see signs]--keeping people in the proper places (modularity)

performing/researching at Place Ville Marie

- professionalism + anonymity: people walk silently alone or in pairs; only person to actively notice me and talk to me was an unprofessional young man (asked "what's that for?" -- the focus is still on utility, not process/practice) ... what happens when people actively notice each other/connect within the corporate space? what happens when I am noticed by/interact with construction workers within the building (neither of us belong there)

- interactions with security--enforcing the way in which this space is meant to be embodied. the unwritten laws which they are enforcing in order to maintain normative corporate behaviour. Asked to move from a busy space because I wasn't moving through it; told I wasn't allowed to sit on the stairs (even though I wasn't obstructing movement), must sit on a bench--enforcing modularity of embodiment of the space

- privileged space: not worried my phone/bags would be taken while I was performing (because overt stealing is not a normative behaviour within corporate space); my privileged body: not treated like a threat; femme presentation + femme labour (needlework) as non-threatening even when acting non-normative--I anticipated this and used it to my advantage

This project is an invitation to re-evaluate your thinking on 'value'

- as early as the Pre-Raphealite movement in the late 19th c, Ruskin & others warned against industrialization and the loss of craft

- Could argue that architectural construction is more important because it ‘makes change’ in the world, ‘progress’—depends on what your connotations of ‘progress’ are; PVM & Montreal have destroyed the natural landscape

- my time cards--I am still valuing my time within a capitalistic mindset... to expect to 'get paid' for everything you do is still a harmful mindset. Even to choose to sell the hours of one's life is to remain trapped (within the grid/cage). What would an alternative be? How do we, metaphorically and physically, stop reconstructing Place Ville Marie?

works cited

Berg, Maggie and Barbara K. Seeber. The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy. U of Toronto Press, 2016.

Colette. Earthly Paradise: An Autobiography. Secker & Warburg, 1966.

“Grids.” Guggenheim, https://www.guggenheim.org/arts-curriculum/topic/grids. Accessed Apr. 2018.

Honore, Carl. In Praise of Slow: How A Worldwide Movement is Challenging the Cult of Speed. Orion, 2010.

Krauss, Rosalind. “Grids.” October, vol. 9, Summer, 1979, pp. 50-64.

Martin, Reinhold. The Organizational Complex. MIT Press, 2003.

Moleworth, Helen. “House Work and Art Work.” October, Vol. 92, Spring, 2000, pp. 71-97.

Richards, George. “The Death of Arts and Crafts.” Canvas, 9 Feb. 2013. http://canvas.union.shef.ac.uk/wordpress/?p=1673. Accessed Apr. 2018.

Robertson, Lisa. Occasional Work and Seven Walks from the Office for Soft Architecture. Coach House Books, 2010.

Ukeles, Mierle Laderman. Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!: Proposal for an exhibition “CARE”. Self-published.

Vanleethem, France, et al. Place Ville Marie: Montreal’s Shining Landmark. Quebec Amerique, 2012.

Wellesley-Smith, Claire. Slow Stitch: Mindful and Contemplative Textile Art. Bratsford, 2015. U of Minnesota Press, 2013.

All artworks cited individually

Performance photographs by Zoe Lambrinakos-Raymond